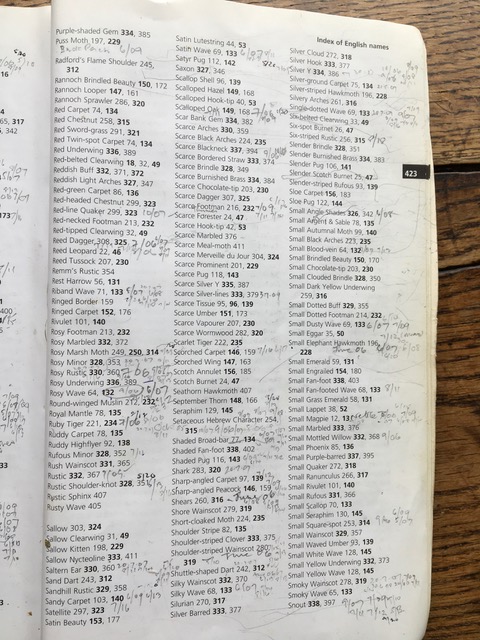

I have in my hands a wonderful book. It was a treasured possession of long-time Shingle Street resident, Tricia Hazell, whose life and memory we recently celebrated. The book is rather battered and weather-beaten (like the rest of us), but has been honoured by years of constant and loving use. Over twenty years use, in fact, as I can deduce from the spidery annotations in Tricia’s hand over lots of the pages. It’s her moth book, a field guide with her dated records of the many moth species that visited her secluded garden at the southernmost end of Shingle Street.

Tricia would often invite over local moth expert Nick Mason and myself to set up an overnight moth-trap and then early next morning inspect the host of bejewelled beauties that had taken refuge there, before releasing them safely into her garden again. Sometimes we’d invite over a larger group of residents to share the experience and the event would take on the character of a moth-séance, with an attentive circle of devotees gasping reverentially at each new winged spirit summoned up and announced by Nick as our moth-medium. Thinking of them as spirits isn’t a bad analogy, in fact. In the ancient world moths were thought of as ‘souls’, which were released from one’s body at the moment of death to flutter away and disappear into thin air. They continue to be magical creatures of the night, whose presence amongst us feels like an epiphany.

One thing that impressed me about Tricia was that she wasn’t, like some naturalists, just interested in identifying the moths and keeping a tally of them. She asked other sorts of questions, too. Whenever we extracted a new specimen from the box she would carefully note the date we’d seen it, but then insist that we pause so that she could discover in her field guide what specific habitats it was found in, what food plants it preferred, and what time of year it would typically emerge. For example, we’d learn that the gorgeous Small Elephant Hawkmoth we’d just caught could be expected ‘between May and July’, was ‘largely coastal’, had a particular liking for ‘heathlands and shingle beaches’, and was attracted to ‘viper’s bugloss, valerian and honeysuckle’. ‘Well, that all fits perfectly’, she’d conclude cheerfully. Although she’d be amazed to hear me say it, Tricia was an ecologist. The word ecology literally means the study of wildlife in its ‘home surroundings’ – that is, in its relationships with the whole web of life on which it depends. And the mark of a good ecologist is not how much you know but in asking the right questions.

Jeremy Mynott

30.3.23