The great eighteenth-century man of letters, Samuel Johnson (‘Dr Johnson’) always made the same New Year’s resolutions:

- Apply myself to study

- Rise early

- Go to church

- Drink less

- Oppose laziness

- Put my books in order

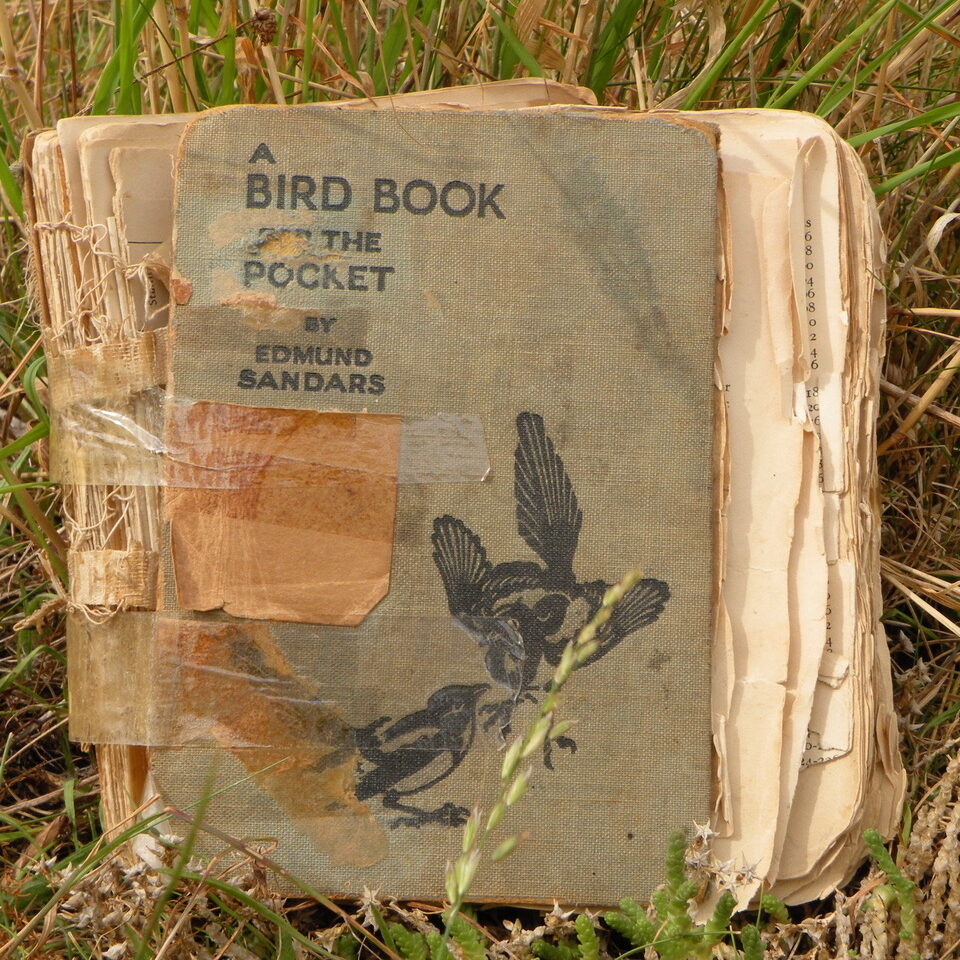

I generally attempt the last one at least, but I then get absorbed in reading my old favourites as soon as I pick them up to re-arrange them. My first real book was a bird guide, Edmund Sandars Bird Book for the Pocket, which I think my parents acquired as a ‘damaged copy’ from the local library. It certainly became damaged quite quickly, as I engaged with it in every way that a five-year old can – smeared, scratched, torn, licked, crumpled, scribbled on and lugged around as my constant companion, indoors and out (especially out). It was my bedtime reading of choice and I made my mother recite it to me endlessly, intoning the potted descriptions of plumage, behaviour and distribution until we both had them off pretty much word perfect. There was not much narrative flow in this, however, so my mother often fell asleep before I did …

I still remember snatches of the text:

Green woodpecker. Manners: has a strong pungent smell, energetic, watchful for enemies when boring, dodges behind trunk. Long, barbed, protrusible, sticky tongue. Never climbs downwards. Sometimes takes two or three backward hops.

I probably misunderstood this nice use of ‘manners’ (habits), and of course I had no idea what the thrilling word ‘protrusible’ meant. Nor have I ever seen a green woodpecker hop backwards. No matter, how could one fail to be enchanted by a world that had such creatures in it. This was a true guide – not a mere book of instruction but my way into the natural world of wonders all around me that I was learning to discover and describe for myself.

I still have my Sandars, just about held together by decades of glue, sticky tape and devotion. Books can do this to you. Jane Eyre, in Charlotte Bronte’s novel, would at the age of ten retreat behind a curtain in the drawing-room to read her favourite bird book, Thomas Bewick’s History of British Birds. She became absorbed in his wonderful woodcuts and illustrations, which fired her child’s imagination: ‘Every picture told a story; mysterious often to my undeveloped understanding and imperfect feelings, yet ever profoundly interesting … With Bewick on my knee I was then happy: happy at least in my way. I feared nothing but interruption.’ A lovely last line.

Buy a child a bird book.

Jeremy Mynott

5 January 2024