We visited the Thomas Gainsborough House in Sudbury the other day. As well as the gallery it has a lovely old garden, once an orchard, with three fruiting trees of great character: a quince, a medlar and, best of all, a magnificent black mulberry whose mighty limbs have been bent down under the weight of years and now rest their elbows on the ground around the main trunk. This mulberry is over 400 years old, so would already have been well established in the 1730s when the future artist Thomas Gainsborough played in the garden as a child. It was one of many thousands imported into Britain by James the First in 1607 to try and establish a silk industry in this country to match that in China.

As everyone knows, silk comes from the silk moth whose caterpillars (silkworms) feed on mulberry leaves and then spin a wondrous cocoon of silken thread to surround the pupa before it finally metamorphoses into the adult moth, Bombyx mori. This raw silk has such special properties of lustre and softness that it became highly prized as a luxury fabric. Hence the ancient craft of sericulture – silk manufacture from domesticated silkworms – that had been practised in China for several thousand years but whose techniques remained a closely guarded secret until, the story goes, Christian monks smuggled some silkworms out of China in a hollow stick around AD550 and presented them to the Roman Emperor Justinian in Constantinople. An early intellectual property theft! The ‘Silk Roads’ from China later became a major trade route to the West, exporting huge quantities of silk and other natural products. No wonder King James wanted some of the action. But he made one big mistake. The trees he imported were all black mulberries (Morus nigra), but any naturalist could have told him that silkworms only feed on the white mulberry (Morus alba), a quite different species, native to China. Well, at least the black ones produced nice jam.

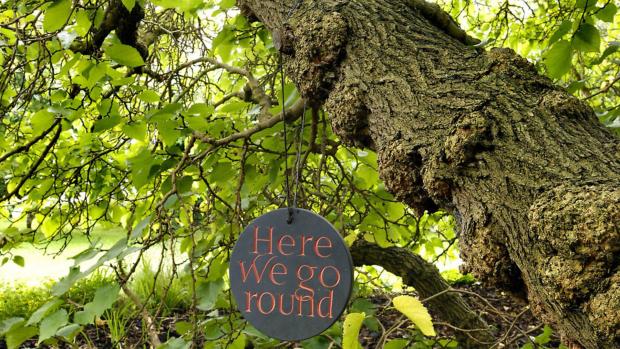

As it happens, Sudbury did later become – and still is – a major centre for silk production in England, though all the silk has to be imported. The black mulberry itself entered English culture in a quite different way, through the nursery rhyme ‘Here we go round the mulberry bush’ in which children are encouraged to get themselves up, washed, dressed and ready for school ‘on a cold and frosty morning’. The lyrics have dubious origins, but maybe here too there’s a mistake a naturalist could have picked up. Could the composer actually have meant a ‘blackberry bush’? Both brambles and mulberries have juicy black fruit, but mulberries only grow on trees not bushes. Hmm.

Jeremy Mynott

5 November 2024