barn owl

Who are the world’s greatest architects? You might nominate the builders of such iconic ancient structures as the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Taj Mahal and the Parthenon, or perhaps modern celebrity-architects like Le Corbusier, Norman Foster and Frank Gehry conjuring up their breath-taking confections of steel and glass. All extraordinary feats of engineering and imagination on a massive scale.

I’d nominate a bird, though. Quite a common one, and very small –weighing just ten grams (about the weight of two sheets of A4) and only 14cm long (of which more than half is its tail). There’s the clue: a long-tailed tit. You can often see loose parties of them in winter flitting through the hedges and trees to work the vegetation for tiny insects and spiders, all the while keeping contact with their family flock through soft, conversational zupp calls and little trills. They are becoming common garden birds too, clustering round the bird-feeder like a fluffy feathered jacket. Their nests are usually very well concealed, deep in blackthorn or hawthorn hedges to protect them from predators, but if you ever come across one it is a thing of great beauty. They construct them from the finest materials – mosses, lichens and feathers (some 1,500 of them in a single nest), all bound together and secured by filigree strands of spiders’ silk. Just imagine sewing with thread from a spider’s web – and using only your mouth. The nest is designed in the form of a perfect oval-shaped dome, with a small entrance hole near the top. It has to satisfy the most stringent building regulations: well insulated enough to maintain a constant temperature for the eggs and young; porous enough to keep the air fresh; capacious and strong enough to hold the female brooding a clutch up to twelve eggs for a fortnight; and then flexible enough to later accommodate the bare, struggling nestlings as they take about another fortnight to grow and fledge. All this done from instinct and at high speed, with no construction manuals, consultants, specialist assistance or tools.

No wonder some of the old country names for the long-tailed tit reflect this remarkable architecture: bum-barrel, bush oven, hedge jug, pudding bag and jack-in-a-bottle. What is even more amazing is that the nest is only occupied for a single season and when the autumn and winter storms come it will be shredded and destroyed. It’s a work of exquisite natural art designed to fulfil its function just once and then to be replaced and newly constructed again the next year. Its only permanence comes from this annual re-creation from the template in the bird’s brain. Surely the winner!

Jeremy Mynott

2 April 2024

It was once all so simple. For centuries people had a pretty good idea of what weather to expect each month and this knowledge was distilled into innumerable country sayings and poetic images. We had mad March hares, April showers, May flies, flaming June and in September we moved gently into the ’season of mists and mellow fruitfulness’. Climate change has undermined some of those familiar associations, however, with unseasonal floods, storms and rising temperatures. It has disrupted the related life-cycles of wildlife, too. Daffodils still ‘come before the swallow dares’, as Shakespeare put it, but they are now as likely to start flowering in February as in March; while the swallows will later struggle to find enough flying insects to catch.

It isn’t all change, though. There is another huge factor, as well as the average temperatures, controlling these seasonal cycles. That’s light. Sunrise and sunset times will remain the same on 1 March 2024 as they were on 1 March in Shakespeare’s day (give or take a minute or two, for tiny variations in the earth’s orbit) and many natural phenomena like bird song are governed by those triggers. The dawn chorus of birds is one of nature’s great wonders. From February onwards you can hear it slowly building, both in volume and variety, as one by one the different species join the swelling orchestra of mingled voices.

The first species to form the choir in February usually include the robin, wren, great tit and dunnock, supported by great spotted woodpeckers in the percussion section. But my favourite of these pioneering heralds of spring is the song thrush, ‘the throstle with his note so true’ (Shakespeare again). There is a clarity, boldness and confidence in its evangelistic mode of address – usually delivered from some prominent pulpit on a house top or tree – which immediately lifts the spirits and reassures you that, yes, the magic of another spring will soon return.

Part of its musical effect comes from the bird’s repetitions on a theme, as Robert Browning noted in his famous poem ‘Home Thoughts from Abroad’:

That’s the wise thrush; he sings each song twice over,

Lest you think he could never recapture

The first fine careless rapture.

And just as the song thrush leads the dawn chorus, so it is often the last bird singing in the corresponding dusk chorus, which is the more muted but equally moving evening performance. In his ‘Darkling Thrush’ Thomas Hardy recalls one that even in midwinter ‘flung his soul upon the growing gloom … in Joy unlimited’, as if it nursed ‘some blessed hope, whereof he knew/ And I was unaware’.

That was the hope of another spring, surely.

Jeremy Mynott

29 January 2024

The great eighteenth-century man of letters, Samuel Johnson (‘Dr Johnson’) always made the same New Year’s resolutions:

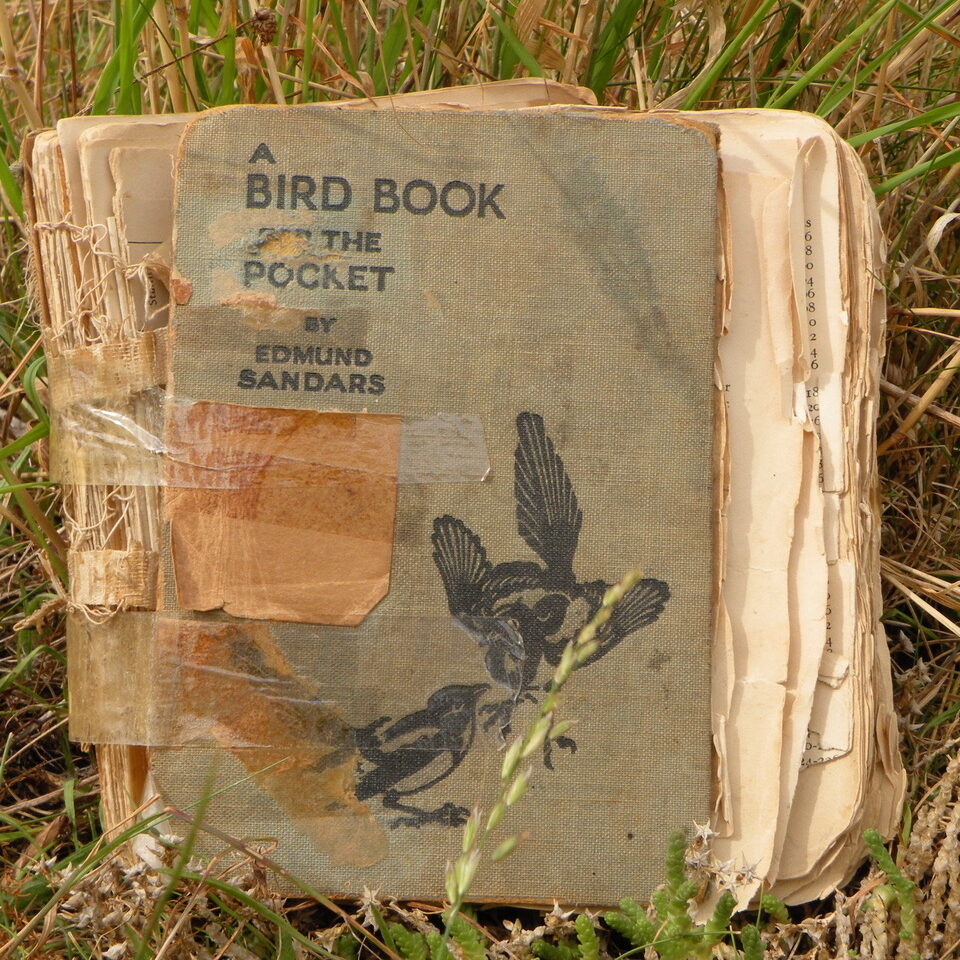

I generally attempt the last one at least, but I then get absorbed in reading my old favourites as soon as I pick them up to re-arrange them. My first real book was a bird guide, Edmund Sandars Bird Book for the Pocket, which I think my parents acquired as a ‘damaged copy’ from the local library. It certainly became damaged quite quickly, as I engaged with it in every way that a five-year old can – smeared, scratched, torn, licked, crumpled, scribbled on and lugged around as my constant companion, indoors and out (especially out). It was my bedtime reading of choice and I made my mother recite it to me endlessly, intoning the potted descriptions of plumage, behaviour and distribution until we both had them off pretty much word perfect. There was not much narrative flow in this, however, so my mother often fell asleep before I did …

I still remember snatches of the text:

Green woodpecker. Manners: has a strong pungent smell, energetic, watchful for enemies when boring, dodges behind trunk. Long, barbed, protrusible, sticky tongue. Never climbs downwards. Sometimes takes two or three backward hops.

I probably misunderstood this nice use of ‘manners’ (habits), and of course I had no idea what the thrilling word ‘protrusible’ meant. Nor have I ever seen a green woodpecker hop backwards. No matter, how could one fail to be enchanted by a world that had such creatures in it. This was a true guide – not a mere book of instruction but my way into the natural world of wonders all around me that I was learning to discover and describe for myself.

I still have my Sandars, just about held together by decades of glue, sticky tape and devotion. Books can do this to you. Jane Eyre, in Charlotte Bronte’s novel, would at the age of ten retreat behind a curtain in the drawing-room to read her favourite bird book, Thomas Bewick’s History of British Birds. She became absorbed in his wonderful woodcuts and illustrations, which fired her child’s imagination: ‘Every picture told a story; mysterious often to my undeveloped understanding and imperfect feelings, yet ever profoundly interesting … With Bewick on my knee I was then happy: happy at least in my way. I feared nothing but interruption.’ A lovely last line.

Buy a child a bird book.

Jeremy Mynott

5 January 2024